One of the things I find I'm enjoying about the figure skating experiments is that the mechanics are entirely crackable by logic. They don't give you a method for much of this stuff, so much as they tell you what the requirements are and leave it to you to work out a way to get there without falling down. The goals are often arbitrary -- "land your jumps on one foot" springs to mind, no pun intended -- but they're also not numerous, or even necessarily all that idiotic. A lot of practical experimentation ensued, and convergent evolution of all the methods tried by all the skaters leads to there being a right way to do something, which is the

most efficient way to do it as well.

It's my favorite sort of game. Here are the rules, you can try literally anything else as long as you follow them. Manipulation of logical systems, more or less.

|

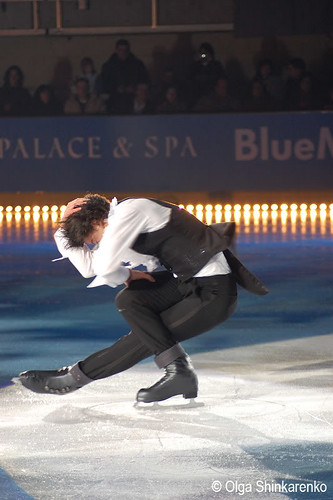

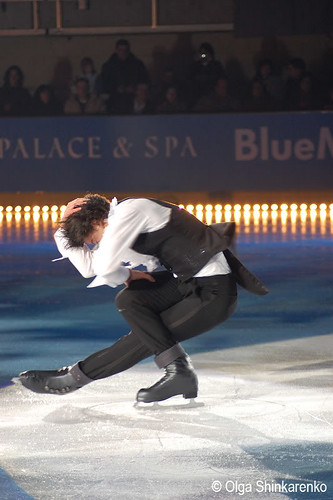

| Stéphane Lambiel |

Take sit spins. There's a bunch of different ways to do them, as you can see there on the left. The requirements are that you have to spin on one foot, and it has to be in a position where the hip of the leg you're balanced on is below the level of that knee. That's it. You are evidently free to do whatever you damn well please with the rest of your appendages, and a lot of skaters do. Free leg sticking out, free leg turned in at the hip, free leg crossed with the ankle on the skating leg's knee, free leg swung out behind you and locked

beneath the skating leg between the thigh and calf, one arm up, one arm out, both arms up, both arms tucked in, one hand holding the free ankle, both hands holding the free ankle, both arms pulled up behind the back with fingers laced together, one arm up and the other one twisted down between your knees. Your head can be up or down or twisted in on your shoulder. Anything you want.

|

| Mao Asada |

The beauty part is, a lot of the details of position that would appear to make the spin harder do just the opposite. I was trying to balance in some of these corkscrews on my bedroom floor earlier; I can get most of them, though I can't hold them for very long. They're minimally stable when stationary, mostly because you have to continually adjust your center of gravity -- breathing is just about enough to knock you over if you're not careful. (People do in fact do this on dry land. It's ridiculously hard. A friend of mine does hand balancing for the Boston Circus Guild, and I am endlessly impressed every time he doesn't fall on his face.) That wouldn't happen when rotating rapidly, for the same gyroscopic reasons that it's nigh-impossible to balance a coin on its rim unless it's also spinning.

|

| Caroline Zhang |

Likewise, you'll notice that most of the skaters are popping themselves up slightly, until the hip of their skating leg is just low enough to qualify as a sit spin under the scoring rules. It looks like showing off; you'd think the efficient (read: lazy) way to keep your weight in a predictable place would be to sit down on the back of the skating boot. It's not. Standing ever so slightly makes it much

easier to keep your weight where you want it. It keeps your muscles engaged, which means you can adjust more quickly. Doing so also makes you press the back of your foot down slightly further towards -- though not actually onto -- the skating surface, which makes it easier to keep your heel in alignment for more or less the same reason throwing 200lbs of salt into the trunk of a rear-wheel drive car makes it fishtail less in the snow.

|

| Johnny Weir |

A lot of the more creatively-twisted variations -- like Weir's knotted pancake spin over there -- look as though they're leaned untenably far from true, mostly to the front. If you try to align the shape of your body along an axis perfectly perpendicular to the plane, you wibble and fall down a lot. You're not balancing a rigid body on a single vertical axis. With your skating leg bent like that, you're balancing yourself on all sides of a series of cantilevered leaf springs. The center of your body doesn't have to be over the point of spin as long as your effective center of mass is.

I thought these were going to be horrible for me, since one of my biggest weaknesses in dance are the various members of the

plié family. It turns out that sit spins lack the requirement that make me so miserable on bendy-dance legs, which is

alignment.

|

Random stock photo

Full plié in second position |

They are adamant in dance that when you're doing

pliés (and odd other things, like some forms of

rondes des jambes), that your knees poke directly out over your toes when bending. No exceptions, do not pass GO, do not collect $200. This is easier said than done, because I'm ever so slightly knock-kneed. It's very common, I have a very mild case, it doesn't affect my gait, and you'd never notice unless you were specifically looking for it. It's helpful in modeling, in fact -- think of how many classic pin-up poses involve pinching your knees together to make yourself look curvier. My natural stance, with knees together and pointed straight forward, puts my feet about 45° apart. I can get my feet and knees aligned if I have to, but it's uncomfortable and feels unnatural. It results in rotational tension around my tibiae, and since I also have high arches, it throws all my weight towards the outside edges of my feet. I can point my feet front, I can point my knees front, or I can not fall down -- pick two.

Pliés are also supposed to be done with your heels pinned to the floor and your spine straight up and down. This is playing the knee-bend level on hard mode for no apparent reason. Sticking your heels flat down, aside from being rather difficult, means you have one less joint (ankle) and one less spring (arch) to adjust and absorb weight shifts. (Standing slightly on your toes is an integral part of the no-hands transit trick. Especially on the bus.) The sit spin positions, even the particularly demented ones, are much more organic.

The most disconcerting part was that, because of the cantilevered-spring arrangement on your supporting leg, your weight has to be rocked much farther backwards than you'd expect. Second most disconcerting bit is that you really must relax. If you have everything tense, then there's nowhere for the muscle to go if you need it to pull you back to center. You can't fall far, anyway -- the floor is like

right there. Aside from that, it seems to be another one of those Atari things:

Easy to learn, difficult to master.

Thanks for the physics of the spins - it makes more sense now.

ReplyDeleteClever.

Alicia

There's a course of the very VERY basic mechanics of figure skating things here: http://btc.montana.edu/olympics/physbio/biomechanics/cam-intro.html It's just the raw (simplified) physics, though -- they don't go through what any of them actually feel like, or touch on some of the more unexpected details.

Delete